It has been said that great expectations often

lead to greater disappointments. Through his first five starts of the season,

Francisco Liriano could not be doing a better job epitomizing that sentiment if

he tried.

Blessed with tremendous raw stuff, enough so

that many wonks figured he could easily compete for a Cy Young award this

season, Liriano has struggled mightily once again with his command, making his

outings as enjoyable to watch as some useless British wedding. In 23.2 innings

of abuse, Liriano has posted a disappointing equilibrium of 18 walks and 18

strike outs. In his first five starts last year, Liriano had tossed 36 innings

with a solid 36-to-13 strikeouts-to-walk ratio and a miniscule 1.50 ERA. What’s

more is that he has already been touched for four home runs, a total that wasn’t

reached until September 7 and required 27 starts to get there.

This year? His peripherals are bad, there’s no

solace in his fielding independent numbers, and he can’t find the strike

zone.

Naturally, Mother Nature was a miserable wench

during his most recent start, sharting snow pellets at the field and making

conditions wretched for pitchers nevertheless, Liriano abided and was cuffed

around by the hot-hitting Rays lineup and was excused from the bitter cold have

three innings and 83 pitches.

After the start, the now 1-4 Liriano tethered

to a 9.13 ERA gave reporters a

self-diagnosis for his woefully start to the season:

"I've got my confidence back. I'm just missing my spots. Just leaving the ball up in the zone. Tonight was a cold night -- not fun to go out and pitch in that weather.”

Unequivocally,

Liriano’s success starts with his fastball. When he is able to throw it over for

a strike on a regular basis, it sets up his slider and change-up. So far this

year, Liriano has struggled mightily to throw his fastball over the plate but

moreover, when he does, it typically is his fastball that is hanging out there

for opponents to slap around.

While Liriano was

never a zen-master of control over his heater last year, he still maintained a

respectable ability to get it over for a strike. That likelihood has plummeted

hard:

|

Liriano’s

fastball command

| |

|

|

Strike%

|

|

2010

|

63%

|

|

2011

|

54%

|

In addition to owning the league’s lowest

strike rate with his fastball, he also has the second-highest well-hit average

(.385) on the pitch as well.

Scouring the video archives, there seems to be

a small yet critical difference in his delivery that could possibly be the

source of his inability to get the ball down. In the first video from 2010,

Liriano dials up a fastball to this particular right-handed hitting Ryan

Spilborghs:

Focus on Liriano in the clip after the

release. During his follow through, he has a significant amount of bend in his

back when finishing, helping keep his offering low in the zone.

Compare that to Wednesday’s delivery:

In this fastball to Tampa’s Sam Fuld, Liriano

remains more upright after his release, not finishing with the same downward

action. The result was a pitch that wound up belt-high instead of knee-high and

crushed to the furthest depths of Target Field. This is a trait that was shared

among several of the other clips from his previous starts this year.

Here is a still-frame:

As you can see, the 2010 version has slightly

more bend helping drive the ball down. Again, it is a seemingly tiny difference

however it could be the distinction between a knee-high fastball and a belt-high

one.

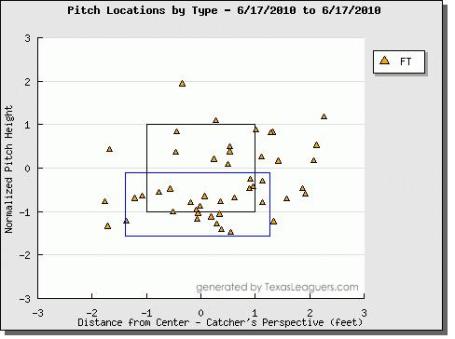

How influential can that minute factor be?

Take a look at the locations of Liriano’s fastballs from those two

outings:

Here we can say that the bulk of his fastballs

feel into the knee-high category. Once again, there are plenty of stray bullets

around the strike zone but a vast majority finished low.

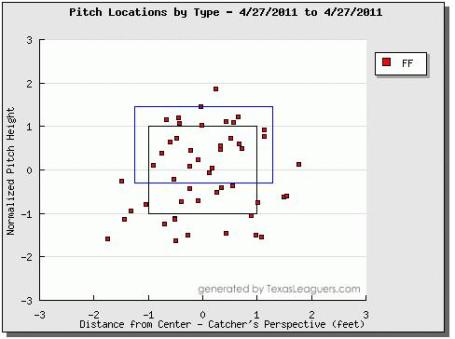

Liriano’s fastball placement on Wednesday was

haphazard at best with a sizeable amount finished up in the zone and over the

middle of the plate.

Why is the difference in Liriano’s delivery? I

don’t know. Certainly there could be a nagging back injury influencing it but

the more likely scenario is that Liriano is still attempting to re-establish the

feel for his mechanics after a long winter away from baseball. When the Twins

refer to his “inconsistent mechanics” this is probably just one of several

glitches they would like to smooth out.

It goes without saying but if Liriano wants to

return to his 2011 form, he’s going to need to locate his fastball in the lower

half of the strike zone on a more consistent basis. My guess? Straight out this

hiccup and we will start seeing him throwing hard at the knees once again.